1. LARS NØRGÅRD DRAWING A

OK, what do we see? A pile of board or cardboard flashes of lightning with a hatched depth effect down in a pair of trousers that obediently go on to become trouser legs (apparently filled with an ordinary leg) and narrow shoes (apparently filled with ordinary feet). And there is a tail sticking out of the trousers, winding around twice and ending up in what one automatically thinks is a (thunder) cloud, though it could equally well be a large powder puff or a poodle’s tail (pretending to be a thunder cloud). The flashes of lightning lean to the left, while the thunder cloud tail twists to the right, and both lightning and tail bulge out realistically under the trousers. It is obvious that in principle there is a contrast between trouser legs and shoes and thunder and lightning, but that contrast is not formulated in the drawing: the flashes of lightning and the thunder cloud are drawn just as meticulously coolly as are the trouser legs and shoes, indeed the set piece flashes of lightning almost more so.

OK, what happens? Not all that much. The lightning figure with the thunder cloud tail just stands there on the paper and hangs out in all his insistent peaceableness. It might be a thunderstorm like an actor patiently waiting between performances. With its big workman’s stomach and poodle tail it could be a pensioned-off thunderstorm without anything to turn to in its retirement apart from dreaming back on past achievements, and perhaps a thunderstorm has only one single chance to make its mark, one single performance in the theatre of the sky before having to retire at an early age like a ballet dancer. It might also be a portrait of the artist as a professional, domesticated thunderstorm with trousers on and a curl in its tail, standing apart as distinctly as one could wish from the amateur bohemians’ sloppy, wanton mucky weather. And first and foremost, there is simply s7ch a fantastic silent commotion over the drawing: melodrama giving a pause for thought; and the lightning figure with the thunder cloud tail is certainly no miserable wretch; on the contrary, there is a glimpse of a certain secretiveness that is not necessarily benign.

2. LARS NØRGÅRD LAND

Lars Nørgård’s drawings are not simply Lars Nørgård’s drawings; they are Lars Nørgård drawings. And Lars Nørgård drawings are not only Lars Nørgård drawings; they are the Lars Nørgård drawings. And the Lars Nørgård drawings are not just the Lars Nørgård drawings; they are a dimension, a sphere, a zone, a universe, a realm, a land on their own, Lars Nørgård Land. And, it should be noted, the Lars Nørgård drawings are not glimpses or snapshots from Lars Nørgård Land: the Lars Nørgård drawings’ collected and still increasing numbers correspond to Lars Nørgård Land, 1:1 or perhaps 1 1⁄2 : 1 1⁄2.

Every Lars Nørgård drawing is an equally important Lars Nørgård drawing among all Lars Nørgård drawings and an equally important figure and event in Lars Nørgård Land, which for all its relative anarchy remains a democratic community. For a new Lars Nørgård drawing will as a rule represent or more correctly constitute both a new figure and a new event; it could also be said that in Lars Nørgård Land a figure is an event and an event a figure, or more precisely: In Lars Nørgård Land a figure is created as an event, and an event as a figure, at the same, clearly portrayed moment.

And as a rule there will only be one figure and one event in one Lars Nørgård drawing, however complex and outrageous it may seem at first (and second) glance. It could well be objected that certain figures recur to a certain limited extent, and of course there are no rules without exceptions, but in the vast majority of cases it will be more correct to say that parts of figures recur, which is the same as saying that parts of events recur, as a figure is an event is a figure etc., and all things being equal the entire drawing is the entire figure and event because as a rule it hangs together in a quite concrete sense with the help of the line; the figure and the event are a calculated upset!

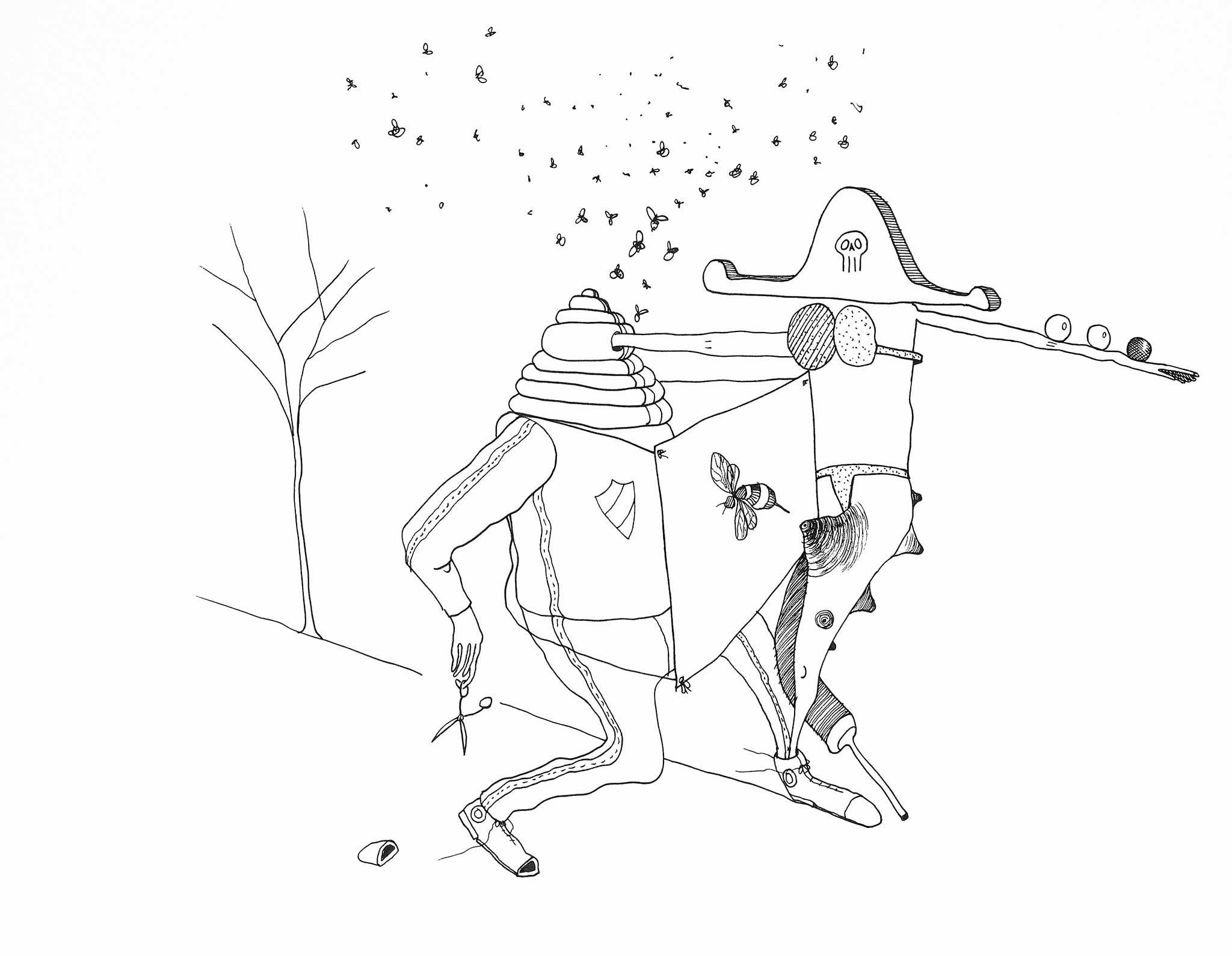

For Figure & Event (let’s call the unit that) always consists of several parts in Lard Nørgård Land. Only occasionally is part of Figure & Event a human being or (potentially) human. In Lars Nørgaard Land the human being and the (potentially) human does not have a privileged status. As part of Figure & Event we just as frequently find celestial bodies, weather, natural phenomena, terrestrial animals, birds and fishes, infrastructure, means of transport, furnishings, painter’s equipment, weapons, kitchen utensils, food and

drink, gaming pieces, sports equipment, electrical installations, measuring instruments, head dress and other kinds of dress and every conceivable kind of other bits and pieces. The human being as part of Figure & Event is as good as a whole human figure and the (potentially) human is a limb or an organ, an arm or an eye, and surely there must be more fragmented than complete humanoids? Once more, we must emphasise, here on a decidedly – what is the fine word? – ontological level, the radically democratic conditions in Lars Nørgård Land.

Figure & Event is a concatenation, a confrontation, an attack, a meeting, a mating, a symbiosis, captured as a mad totality: A conflict as itself. For irrespective of whether in relation to each other the elements behave harmoniously or antagonistically, explosively or implosively, in a complicated or straightforward manner, they remain fixed in their confounded, wretched co-existence, something of which they are quite aware and not profoundly resigned to, rather quite intoxicated with. For however often Figure & Event seems to spell Minotaur & Blind Alley, this does not alter the fixation’s character of hilarious and acute excess: Figure & Event is a monster about to leap, in and from itself, to put the struggle metaphor on its head now, not springing, not not springing, but springy and about to spring. An essential concept in Lars Nørgård Land, perhaps its very oxygen, is humour, which is unfortunately also the most difficult concept to define (and the most difficult gas to find a formula for). Contrary to all common sense, this Figure & Event takes place of course again and again and all the time at home in Lars Nørgård Land, where the Lars Nørgård drawings reside and eyes pop out of heads.

And Lars Nørgård Land is black on white in black-and-white like television in the old days and drawings at all times.

3. LARS NØRGÅRD DRAWING B

OK, what do we see? We start on the left-hand side with a clothes line that suddenly turns up out of nowhere. A peg hangs on the clothes line holding on to the tip of a net stocking that is stretched fa-a-a-a-r up and out of the foot it is still being worn by and which, the foot, therefore sticks straight out in the air, rather like a goose-step. The foot continues on the right into a trouser leg on which a chestnut animal with a big chestnut body, a little chestnut tail, four little chestnut paws and a little chestnut head with a tiny chestnut snout and two weeny chestnut antennae, all with a three-dimensional hatching effect, stands and stands. Then it is most practical to jump up again on to the clothes line, which goes right in to the nostril of the pointed nose of a head seen in profile that is dominated by an open eye overflowing with tears, but also includes a little mouth pursing its lips and surrounded either by wrinkles or stubble. Above the eye the line producing the profile continues to the right but then simply comes to a halt and hangs there flapping about in a quite different direction from the straight back that starts (or finishes) a good way further down. Under the mouth a little chin in the profile is indicated just by the start (or finish) of the back, but there’s no neck. The profile line continues down a little and then turns sharp left with a shadow effect indicating fabric (on top of clothes or body), whereupon it zigzags down and then goes obliquely to the right forming a point that goes on in to the left until it meets the line denoting the back. Just beneath the point on the profile line’s first sharp bend, a new line continues in a downwards direction and in under the second, long point of the profile line and further down, where in a zigzag with long shadows it turns out to be the other trouser leg going on out into the other (bare) leg and the other foot in the other, holed net stocking. After the zigzag, the trouser line goes up and then sharply to the left and then zigzagging up and then sharp right, turning into a hole in the trousers in which a pair of striped underpants can clearly be seen. The trouser line continues up and meets the back line. And that’s that. Apart from a tiny circle just about on a level with the chestnut animal’s legs, which could be a trouser button or a navel. For while – how shall we put it? – the extremities are individually well under control: the clothes line into the nostril, the nostril in the face, the net stocking in the peg, the foot in the net stocking, the chestnut animal on the trouser leg, the hole in the trousers, the underpants in the hole in the trousers, the zigzag tearing off of the other trouser leg, the other foot out of the zigzag tear, things go completely haywire in the centre that is intended to hold the extremities together (and hence the detailed description above), for what is body and what is jersey and what are trousers here? And how is it the head on the left simply stops so that the profit line hangs flapping there like a limp continuation (out through the eye!) of the clothes line…?

OK, what happens here? One can obviously talk of a man in difficulties and torment: You can only believe that it hurts more than usual to have your foot hung up in a clothes line from your nose. Then the humiliation of having net stockings on and a hole in your trousers is of less importance, but on the other

hand it is also obvious that the first misfortune of having a foot in a clothes line in your nose is connected to the second and third, wearing net stockings and having a hole in your trousers. This is a man who is the victim of massive humiliation; far more than being henpecked, he is compelled by his wife to wear net stockings, for surely there is an invisible woman in the background in the drawing represented only by the blankly staring chestnut animal with all its threatening connotations relating to Christmas and domestic bliss. But however suspended and exposed to contempt this net stocking man is externally, he is equally broken and crazy internally, where he is partly a large, white hole and partly is lost in himself and his guises in a quite labyrinthine fashion; it is in fact most likely that in the pure logic of drawing this oh so bared and weepy face is part of the outermost piece of disguise, and the real face, if such a thing exists, is hidden far, far away. Poor, poor net stocking man.

4. LARS NØRGÅRD ARCHIVE

When it was decreed above that Lars Nørgård’s drawings are Lars Nørgård drawings, which are the Lars Nørgård drawings, it wasn’t quite true: There are or especially were drawings by Lars Nørgård that neither will not can be included among the Lars Nørgård drawings. In addition there is the fact that the Lars Nørgård drawings have a history behind them, which falls into two chapters or tempi or types: Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings and Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings; the drawings described and interpreted above are Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings and, as will be seen, it is not everything that can be said about Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings that can be said about Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings and vice versa. Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings are a chapter long since closed, and all new Lars Nørgård drawings are Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings, but on the other hand this doesn’t mean that Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings are not just as much Lars Nørgård drawings although they themselves would perhaps deny full membership; they are full members, and they are that before anything else: Lars Nørgård drawings first and after that Style 1 and Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings.

Central to Lars Nørgård’s art is a duality, sometimes a conflict, between figuration and abstraction. The Lars Nørgård drawings are figurative; drawings by Lars Nørgård that neither can nor will be included among the Lars Nørgård drawings are abstract, so simple is it in fact. At least almost, for in the beginning there are a few exceptions, but only from the rule that non-Lars Nørgård drawings are abstract. And over the last eight years the division of labour in Lars Nørgård’s art has been as clear as a bell: the paintings are abstract, the drawings are figurative (the only abstract drawings nowadays are sketches for paintings, and they know perfectly well that they are not Lars Nørgård drawings). But the road to this resolved situation has been long and winding and is not to be mapped out in all its detail here, where the focus is on the drawings.

A little biography: The drawer himself, Lars Nørgård, was born on 25 October in Aalborg; from 1975 to 1978 he studied at the Danish School of Art and Design in Copenhagen; 1980-81 in the Academy of Art College in San Francisco; back in Denmark he became a member of Værkstedet Værst and thus one of the famous “wild young things” that took the Danish art scene by storm at the beginning of the 80s. Motivated by their generational confrontation with the political and conceptual art of the 70s – and with solid inspiration from the most recent trends in Germany, Italy and the USA – the “wild young things” rediscovered both figuration and the classical disciplines, painting and drawing. The result was a kind of jaunty expressionism with a glint in the eye, to which Lars Nørgård fraternally attached himself with all his youthful energy.

Lars Nørgård’s very first public drawings, as they can be seen in the exhibition catalogue Can a woman he happy with a new-wave haircut, 1984, are one big jumble containing both scamped, “clumsy” abstraction and grimacing, “naïve” figuration and quite a lot in between, and then some more peaceful figure pieces, politely copied from classical models.

About 1985-87, both paintings and drawings by Lars Nørgård change character. The paintings become stylised, caricatured portraits and/or enigmatic tableaux; the drawings turn into the first Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings and can be seen in the exhibition catalogue Circe, 1987, and the book of drawings entitled Arch Support, 1987. Apart from a couple of pieces in the Circe catalogue, the drawings are more stylised than caricatured (and never portraits), and they all present themselves as enigmatic tableaux with one or more human figures in the main roles (and just occasionally animals in secondary roles). Lars Nørgård has later talked of this period as a “sourishly amusing” phase because the characters have such “little prim, cross, taciturn mouths”, and so they certainly do, too; they look one and all extremely melancholy. Just as the actual drawing style is deliberately stiff and shaky in a special “80’s Italian” manner (Clemente, Cucchi, Paladino and Co.).

All this is in contrast to the things or non-things that actually take place in the drawings, for by way of contrast to Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings, figures and events are not one and the same thing; the figures are a host of elongated, poker-faced Buster Keatons m/f who are exposed to – or are forced to undertake – all kinds of comically crazy acts or non-acts by the invisible drawing instructor LN. One instance in Arch Support, for instance, shows on the left a man standing on his head with a tilting bowl of water balancing on his feet and round his stomach a lifebelt that a little girl is blowing up, and on the right a naked man whose underpants have suddenly burst off him and now are on their way up through the air accompanied by racing stripes.

The chapter on Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings was interrupted in 1988 by a host of non-Lars Nørgård drawings that are both called and are doodles and can be seen both in the exhibition catalogue Vamos a ver, 1988, and the catalogue/book of drawings Krimskrams, 1988. The “doodles” are over-drawn total drawings, full of curlicues, in which figurative contours and fragments can certainly be discerned, but never emerge as the main component. With a precise image, Lars Nørgård has subsequently talked of “the drawing as an effervescent tablet” in which “ideas pop up through the doodle soup like diving ducks”. He paints semi-abstract during this period and as in the later total drawings from the mid-1990s, the drawings act to a high degree as models and basic ideas for the paintings, as working drawings, so to speak.

After the transitional phase of doodling, there is a return to the Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings, but in a looser, more unruly, what-can-we-think-of-now manner, as can be seen in the exhibition catalogue/book of drawings Kikeriki, 1989, and the book of drawings entitled Massage, 1992. The Italian Buster Keatons no longer automatically play the main part in a straightforward scenic tableau. The animals and the bits and pieces acquire an independent life and come dangerously close to the Buster Keatons. In Kikeriki, a fish and Buster stare each other out, while in another Buster is halfway a fishing rod. And things get entirely out of hand in Massage, where a stitched sausage hangs over a forehead that hangs over a head, which is (probably) a pile of hairy pancakes, and a fishing line with a fish on the end forms an ear and is fixed to a cotton bud, and two vultures or flamingos sit on top of a pair of trousers with legs in and shoes on, and a man with a cat’s head has a Mickey Mouse penis sticking out of his trousers.

A work that both clearly and confusedly marks the transition between Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings and Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings is the text and picture book by Lars Nørgård and Vagn E. Olsson, The Flood, 1990, which emerges as a swirling tabernacle of inventive ideas, whole and partial, all mixed together. Among other things we find a two-page-long strip cartoon about a bowling ball which, by crushing three sausages, becomes a globe rolling off towards the sunset, but is crushed by a weight and turns up again and mutates into a weeping sailor – something that anticipates both the cartoon films Art Support, 1994, and Æbleflæsk, 1996, and the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings. But there is also a large number of – especially small – drawings in the book, which in all their improvised Buster-free haste throw more than a passing glance at Style 2.

The final step towards the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings is taken in a lengthy progression from about 1992-96 and in the crossfire from a confusion of extra-artistic commissions and projects: To begin with, the work with the two cartoons mentioned above, which demanded a far more assured and flexible line than the nervously artistic line of Style 1; secondly illustrations to Claus Christensen’s and Søren Wedderkopp’s two cookery books Nedkoges til passende smag og konsistens, 1995, and PORCVS SUM, 1996, to Jens Engberg’s history of the theatre Til hver mands nytte, 1996, and to Henrik Nordbrandt’s diary Ruzname, 1996. At the same time there was an intense interchange with painting which between 1990 and 1998 had again become figurative and in 1995-98 led to a kind of painterly realisation of on the one hand specific figures and motifs from the cartoon films and the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings and on the other of the Style 2 approach as such, or was it the other way round? There are several examples of the transport of motifs from Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings to paintings and cartoons and to Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings, not least among the important, tiny vignettes to Henrik Nordbrandt’s diary.

Contributory to getting the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings started and moving forward was also Lars Nørgård’s annual visit to Israel for treatment (for psoriasis), especially between 1993 and 2000, when, between six and seven o’clock in the morning in hotel room 119, he produced drawings like one possessed before going out and embarking on his inhuman, day-long sunbath. (Since 2004 his drawing refuge has been the rather less restrictive blue lagoon in Iceland, where the drawings simply pour out).

The development of the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings can be followed in the exhibition catalogue and book of drawings entitled Vand under broen, 2001, which brings together drawings and sketches for

paintings and realised and unrealised storyboards for cartoon films from 1993 to 2001. Even among the earliest drawings there are already incisive Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings, for instance from 1993 a drawing of a canvas with a hole in it, whence a horse’s tail is fluttering and hovering about a tail-less horse’s rump; most drawings from 1994 are storyboards; 1995 is not represented, and 1996 scarcely at all, but from 1997 the good style progresses increasingly smoothly and without friction.

The most important characteristics of Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings in relation to Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings are three in number: a) the clear, distinct, perfect manner of drawing, which is actually more closely related to the cartoon film than the strip cartoon (instead of Disney, anarchic folk like Tex Avery and in a Danish context artistic cartoonists and illustrators such as Storm P., who made the first cartoon film in Denmark, and Arne Ungerman, who illustrated the nonsense poet Edward Lear); b) the imaginative bringing together of the drawing’s motifs to form the unity we call Figure & Event; c) the dethroning of the elongated and Italian Buster Keaton principal figure and the replacement of him with whoever and whatever as parts of Figure & Event (if as good as whole human figures take part in Figure & Event, they will now be small with large, grimacing heads, for, as Lars Nørgård has said later, “the facial expression is the most important, and the body is really only there to support it, like a little painter’s stool”).

Lars Nørgård had a quite different sudden and visible breakthrough in 2001 when within no more than a fortnight he was commissioned to decorate the new café in Statens Museum for Kunst and formatted Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings for eight large and simple canvases and also designed a crowded Style 2 tablecloth. That “sharpened my pen”, Lars Nørgård commented, “like a gigantic practice session”; now there was no motorway back: “Getting this café to succeed gave me confidence in the direction the drawings have taken, so that all crazy ideas could be incorporated without any danger of being beaten up by the others in the long breaks between lessons”.

And as said above, he has drawn and drawn, and there are no signs that he is going to throw the inkwell into the ring just for the time being.

5. LARS NØRGÅRD DRAWING C

OK, what do we see? Well, if only I knew where to start. Perhaps with the little fish sitting between toes reading a book. And if only I could be content with that, for that’s certainly plenty in itself, but I’m afraid not. The toes continue into a foot that continues into a leg that disappears in front of (and perhaps belongs to) a cowboy whom we see from behind and whose head is completely hidden in a vast cowboy hat. A couple of vertebrae are bulging out on the cowboy’s back, and he has a cartridge belt round his waist. Whereas the first leg is forced to be rather intricately twisted if it is to be the cowboy’s, the other leg is clearly and without interruption fixed to the lower part of his body; on his foot he has, reasonably enough, a long, pointed cowboy’s boot. Nor is it entirely straightforward with regard to what is perhaps one of the cowboy’s arms (the other can’t be seen at all), which goes straight down along the side before turning at the elbow and suddenly growing huge and going on out of his shirt sleeve, on which there is a splendid cuff link, and straight up in one of the holes in a pair of bathing trunks decorated with ear-like bows, as though this arm were a leg instead. But who or what is wearing the bathing trunks is really a difficult question to answer: it is a light, oval ball or planet or simply a sphere decorated again with lighter fivefold oval rings rather like rings in the water – I can’t get any further. A leg is sticking out of the other hole in the bathing trunks and disappears behind a swimming ring or a tyre with a star on that leads from the sole on the cowboy’s cowboy boot to the side of that same cowboy boot, and so appears not to hang together. Below the swimming ring or tyre, a family of fish, a grown-up and four children, are looking up at all this confusion and creating rings in what then must be water. The first foot, bare and with the fish between its toes and only perhaps belonging to the cowboy, rests on the gable of a house with a little window. His backside on the other hand, the cowboy is again resting on a somewhat unclear entity that most of all resembles a mixture of a bicycle handlebar (with small crosses on it?) and a sucker and a chimney and one of those little electric prodding sticks used to get the bulls going in a rodeo (when directly asked, Lars Nørgård maintains it is a vacuum cleaner, so now we know!). And well, yes, a line goes from the gable in under the handlebar thing (the vacuum cleaner!) and over to the swim ring/tyre.

OK, what is happening? Quite a lot. If we stay with the fish, the family of fish could be looking longingly at the man in the house that is the fish between the toes, who voluntarily or by force (from the cowboy) has had to desert the family for a life in the service of literature; I know that feeling myself in any case! It might well be more sensible to start out with the cowboy as an unrealistic bloke with his head high up in the hat (it is unrealistic in itself nowadays to act the cowboy, but is it not exactly someone of that sort who is the US president at the moment, so perhaps this is a political drawing!?), which is fragilely extended between art (he can of course in principle also use the fish as a pen to write in the book), which is comical and second-hand (or -foot), and daydreaming, the curious globe or ball in the bathing trunks, which is absurd in a slightly disturbing and twisted erotic fashion. Midway between these extreme escapist positions there are the quite hopeless realities that literally flow between land and water, house and sea. And perhaps the cowboy ought to choose the house and put his hands on the bicycle handlebars chimney (vacuum cleaner!) or perhaps he ought to choose the sea (and return the fish to his family) and jump down into the lifebelt/tyre, but inside the black hole of the cowboy hat he doesn’t see any of these possibilities, the fool.

6. LARS NØRGÅRD DEMOGRAPHY AND DIVERSITY

We are not going to undertake a census of things and animals and human figures here, for on the present basis it will simply be impossible to delimit the precise, official number of Lars Nørgård drawings, and in any case there is a constant stream of new ones. Instead, it might be an idea to attempt an overview over the various types and kinds into which the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings can be organised and to glance at the works associated with the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings (which have the potential for gaining citizenship and being naturalised in Lars Nørgård Land), which are not (as a matter of course) drawings on paper, and which in Section 2, which was only about drawings, we pretended didn’t exist; on the other hand, several of them were pointed out in Section 4.

The Lars Nørgård drawing is done with Chinese ink, Indian ink, fibre pen or ball pen on (preferably acid- free)paper in sizes including A4, A3, 39 × 40 cm, 32 × 24 cm, 28 × 34 cm, 24.9 × 21.5cm, 24 × 15.9cm, 23 × 30.5 cm, 20.9 × 29.6 cm, 18.9 × 17.4 cm, 18 × 21 cm, 17 × 25.5 cm and 15 × 21.2 cm. Putting it into (other) words, a Lars Nørgård drawing is a quite ordinary modest size in relation to the often quite huge paintings; and, as can be seen for instance in the catalogue for the group exhibition Clinch, 2004, Lars Nørgård loves to hang his Lars Nørgård drawings up in large, dense accumulations extending from ceiling to floor.

The easiest, but also the most sensible way of arranging the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings is to be guided by the degree of simplicity or complexity, airiness and density in the drawing, or even more simply (in principle, but not in practice) the number of parts in Figure & Event. The lowest possible number of parts is two, and these simplest and airiest drawings will often emerge as visual witticisms, which, if I may say so, immediately say what they mean: the fly swatter plant and the fly, the flying winged weight. After this, any number of parts can be added or perhaps rather come into bud and make Figure & Event increasingly complex and increasingly dense. I don’t think it’s possible to count your way forward to the largest number of parts that can constitute a Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawing – the limit is where it is no longer possible to distinguish the individual parts from each other (which is not necessarily the same as seeing what it is they represent, just look at my helpless readings above and below). Beyond the limit there are the sketches for paintings that we have called total drawings, and which perhaps to a greater extent than the actual paintings can be read as accumulations of specific, figurative parts – and not merely abstract “shapes” – but the absolute centrifugal quality of which remains alien to the drawings; Figure & Event get hopelessly lost in that kind of busy pictorial mists.

Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings do not repeat themselves, but as said above, they at first repeated some of the Style 1 Lars Nørgård drawings. What is frequently repeated are parts of drawings, and there is no doubt that certain parts are more popular than others, sure hits for instance being fly swatters and chessmen and electric light sockets and golf balls and clocks and hens and cars and pigs and globes and playing cards and tennis rackets and umbrellas and all things Cowboy and Indian and mountains and bees and fishes and sleeves and skis and ties and ducks and doors and cubes and hats/caps and snowmen and crocket mallets and canvases and targets and trousers (with holes in them) and plasters and rabbits and trains and signs and cacti and lighted candles and (artificial) shark fins and nails and screws and ghosts and balloons and skittles and horses and Christmas trees and brushes and keys and scissors and cameras and cucumbers and hearts and feathers and butterflies and rifles and medals and snails and houses and tents and bath tubs and sausages and dogs and plaits and chairs and boxing gloves and combs and magazines and lawn mowers and stamps and letter boxes and matches and paper boats and accordions and lightning and reed maces and ferries and rulers and sandwiches and bicycle tyres and chestnut animals and sugar lumps and flags and women and water. And just as the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings as such remain open to everything and everybody, the group of favourite items can also constantly be extended, a recent addition being the chestnut animal; on the other hand they rarely go out of fashion: both in the very first and very latest Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings we find for instance keys and sticking plasters and (artificial) shark fins. To attribute to these favourite items symbolical, allegorical or art-historical (targets = Jasper Johns) meanings will be futile: the only thing that as a single whole characterises parts and favourite parts is their radical ordinariness and banality; that is what makes them so special and so specially Lars Nørgårdian.

Nor do the major, characteristic and repeated partial complexes that we call recurrent figures (minus event) appear in Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings. Or hardly, for in the crossfire of the first phase there was – especially in the paintings and of course in the cartoons, but also affecting the drawings – an exclusive group of recurrent figures including the sailor, the hunter pig and the long-capped caddy. And then there is in fact suddenly a number of recurrent figures in action in the very latest drawings, and completely contrary to the system I have introduced, they come across each other somewhere as individual figures; one of them is the woman Lars Nørgård calls “Kirsten the leisure pirate” with the billiard queue wooden leg, another is a “wasps’ nest jogger”. And then doesn’t “teaspoon head” also appear in more than one drawing? I daren’t look.

The works associated with Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings are licensed both to operate with recurrent figures and to steal motifs (Figures & Events) partially or wholly from Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings and each other. And to use colour. We can start with the most loyal works, the eight paintings in Statens Museum for Kunst, 2001 (and the seven paintings from the previous year (five of which are identical to the SMK paintings), which can be seen in the exhibition catalogue Grundstødt forskning, 2000), which are simply inflated drawings with whitened background as in the SMK paintings, and with extremely discreet colouring here and there. Then there are the illustrations to Henrik Nordbrandt’s diary Ruzname, which are Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings en miniature, and to the two cook books, Nedkoges til passende smag og consistens and PORCVS SUM, which are Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings with respectively soup and pig themes (in the pig drawings, a pig wearing spectacles is a recurrent figure); here we could also mention the coloured DSB posters, 1999, which are Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings on the theme of trains.

Then there are the paintings c. 1995-1998, which are painted, usually expanded or accumulated versions of motifs (Figures & Events) or motif parts in Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings (or conversely). A particularly important place is occupied by the tablecloth for the SMK café, 2001, and the wall decoration to the assembly hall in the Lake School, Skolen ved Søerne, 2006; in both places there is a host of Lars Nørgård drawings, most of them repeats, on show at the same time, on the tablecloth in miniature, on the wall in inflated dimensions, and not like large accumulations of Figures & Events, but neither without to a certain extent a binding contact between the individual motifs. As though the drawings in a normal group hanging had burst out of their frames and got together in earnest. We shall probably not come closer to an idea about how the impossible panorama view of Lars Nørgård Land will look, and, I can tell you, it looks simply fantastic. Finally, there must in this loyal distribution be a space for two small sculptures: “Can I have a spoon”, 2003, which can be seen in the exhibition catalogue Ventilation og vemod, 2003, and “The Soup Hunter”, 2004, which is to be seen in the exhibition catalogue Clinch, which are sculptural versions of two classical Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings representing respectively an egg with spoons in the lining of a pair of trousers and a hen with a shark’s fin on its back.

In an intermediate section there are the coloured illustrations to Jens Engberg’s Til hver mands nytte (watercolours) and Helle Helle’s rhyme & ditty book Min mor sidder fast på en pind, 2003, which relate to the contents as direct illustrations, but all the time via the approach in the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings; for instance a watercolour in the Engberg book represents someone who with a knife has just taken a piece out of his heart, which is fixed at the end of his neck.

The next section is about works that make a story out of the Style 2 Lars Nørgård works, which of course the drawings themselves simply refuse to do; they are poised to become Figure-Events. The black and white film Art Support is constructed as a kind of transformation baton from one motif (Figure & Event) to the other: Fat man with gun and no head, watering the plants through the holes in his stomach and becoming a thin man with a large tomato as his head. While the black and white film Æbleflæsk, 1996, like the story boards in the book of drawings Vandet under broen, is its own free-wheeling story in an animated Style 2 with several recurrent figures. There is not terribly much epic oomph in the computer-animated film Lost at Sea, 1999, in which the figures, scenes and approach seem to be inspired by the 1995-98 paintings rather than by Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings. Finally, there is the children’s book Princesse Langskæg, 2002, in which the coloured Style 2 drawings illustrate Lars Nørgård’s own off-beat story about Princess Rebekka, who wakes up one morning and to her horror discovers she has grown a beard: at one point Princess Rebekka and her brother Prince Henning and the Tease come past the so-called picture forest, where coloured miniature versions of the greatest classics among the Style 2 Lars Nørgård drawings plus what seem to be a couple of new ones are hanging out to dry and on show. And, as Lars Nørgård writes:

“The Tease is left behind. Not because he looks at the pictures growing on the trees, but because he is looking for something quite specific. For it was here in the picture forest he once wandered off from his mother and father and got lost.”

And so I will not adopt a stance on how it all relates (and doesn’t relate) to the extra large drawings painted on and dripped on with watercolours, which see the light of day for the first time in this book. You can do that for yourself!

7. LARS NØRGÅRD DRAWING D

OK, what do we see? An unusually broad-mouthed rabbit head with nose and whiskers and with fingers instead of ears sticking out of a half-mask from which no eyes are peering. Out of the wide, half-open mouth sticks the bottom part of two trouser legs (apparently with legs in them), which continue down into two shoes (apparently with feet in them), which seem firmly planted on the ground. The line marking the rabbit’s head continues urealistically in over the trousers, indeed it does.

OK, what happens? Or rather: what has just happened? Has a rabbit’s head without ears and without a body just carried out a hold-up (the half-mask) on a man and eaten him lock stock and barrel and used his legs as legs and two fingers as protruding ears? Perhaps, in view of the wide mouth, it isn’t a rabbit’s head, but a disguised frog’s head with the nose and whiskers painted on. The unrealistic line of the chin suggests that either the legs (and the shoe) or the rabbit’s head is a ghost, perhaps both the legs (and the shoes) and the rabbit’s head are ghosts and only the ear fingers real. Outstretched first and middle fingers constitute a triumphant V sign (v for victory), and it can naturally be the rabbit’s head that is triumphing after its gluttonous atrocity, but it can also be the devoured person who has managed to keep alive inside the rabbit’s head and therefore is raising two fingers in triumph, which, with a true irony of fate, simply complete the rabbit’s head. And who says that it is a first finger and a middle finger, it can also be two middle fingers saying a double “fuck you” on behalf either of the rabbit’s head or the human being. But soon the rabbit’s head will discover that it is not only impolite, but also extremely difficult to talk with legs in your mouth, and in fact fingers are not good at wagging. The rabbit’s head is a scoundrel that isn’t lacking in charm, but he is caught in a trap, the trap which the finger-ears form together.

8. LARS NØRGÅRD SIGNS AND DEEDS

The Lars Nørgård drawings are necessary on account of their precise and insistent superfluity. No one in their wildest imagination has been able to imagine them, and heaven knows that no one has asked to see them, but once produced to our depraved eyes, they are not to be got rid of again, never ever. And then if only the form was artistically expressive and impressive, scratched and erased, but it isn’t, it’s highly polished, stylish, elegant and virtuoso to a T, fully on a level with whatever the big, commercial cartoon film factories can boast of, even on a good day. And if only the motifs (Figures & Events) were artistically exotic and boundary-crossing, spectacular and coarse, but they are not, they are completely daft and meticulously picture-lottery-combinatory nonsensical. And if only the drawings then were artistically serious and sober, but they aren’t, they are simply excruciatingly funny just like that. If they were only art, but they aren’t, they are the Lars Nørgård drawings. No mercy and no shame and no possible defence.

I have deliberately avoided a single word that otherwise seems indispensable when talking about the Lars Nørgård drawings, that is to say surrealism. Partly because the Lars Nørgård drawings are not surrealistic, they are Lars Nørgårdian. Partly because the Lars Nørgård drawings do not have a project in common with surrealism; there is no subconscious truth here to reveal or catch off balance; here there is on the surface an immediate, continuous confusion of bizarre generalities. We can compare them to the surrealists’ party game of “Cadavre Exquis”, where of course a number of artists all draw on the same piece of folded paper, and first one draws on his bit and continues a short way over the edge, and then the next goes on blindly from the edge etc. In the Lars Nørgård drawings, the drawing plays “Cadavre Exquis” with itself, at a flash and with open eyes. The exquisite cadavers are trampoline artists who have come to grief and got hopelessly lost in fleecy clouds.

9. LARS NØRGÅRD DRAWING E

OK, what do we see? A ferry (with a funnel issuing square smoke, with a screw that is not in the water, with a cork that leaks) and a cap (with the letter F (for Ferry, not Fenomenology) and a beak ( perhaps a piece of tart siamesically linked to the cap) and a whistle (which is letting one drop and whose holes mimic the portholes of the ferry, or the other way round) and half (the lower half) of a swimmer and a tie (that the swimmer is climbing up) and a book of music (which the water is pouring down on and mixing with) and a sea/a cloud (or the other way round), and it all hangs together.

OK, what happens? A smoky, saucy hip hop ferry with noble dreams of swimming puts up a smoking finger and much against its will leaks a wet symphony.